Why Skipping 1:1s as a Manager is a Terrible Idea

A list of 6 non-obvious side-effects of managers skipping 1:1s with their reports.

Welcome to the Captain’s Codebook newsletter. I'm Ilija Eftimov, an engineering manager at Stripe. Each week (or two) I write a newsletter article on tech industry careers, practical leadership advice and management how-tos.

As a new engineering manager, there's one maxim I've read in all writing on management 101: do not miss or skip 1-on-1s with your reports. This maxim appears in different forms, but the message is always the same. Some say, "Miss them at your peril". Others call them the "highest-leverage meeting of your week".

Steven G. Rogelberg frames 1:1 well in his HBR article Make the Most of Your One-on-One Meetings:

The best managers recognize that 1:1s are not an add-on to their role—they are foundational to it. Those who fully embrace these meetings as the place where leadership happens can make their teams' day-to-day output better and more efficient, build trust and psychological safety, and improve employees' experiences, motivation, and engagement.

With Nvidia's rise in popularity, all of us have paid much attention to the CEO's practices. Notably, Jensen Huang has 60 direct reports and doesn't do 1:1s. He believes that at _that_ level, he should give feedback publicly. He considers it "a gift for everyone to learn from everyone's mistakes". That sounds great, but let's face it: You and I are not Jensen. Nor does your company have Nvidia's culture. I don't work there, but I'm sure he's an outlier, even within his company.

High-level leaders leverage vision and influence to lead. And what's a better way to articulate the vision, get feedback from reports, and align on the messaging than via a 1:1 with the people who will spread that same vision through the ranks?!

Experienced managers fall into this trap. They believe they're the outliers. They prioritise other meetings over their 1:1s, effectively prioritising process over people. They think that attending that one review meeting is time better spent than talking with their own reports. They believe that one escalation—usually just a wild goose chase—can't be delegated. They make up this excuse that "a new crisis requires their attention." So, they decide to skip.

All to their peril.

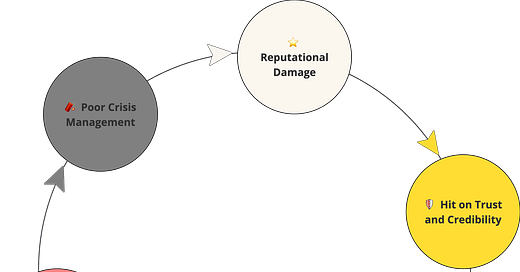

In continuation, we'll cover a list of non-obvious side-effects and downsides of engineering leaders skipping 1:1s with their reports, specifically:

⭐️ Reputational Damage

🛡️ Hit on Trust and Credibility

🤝 Weakened Team Morale and Engagement

⚖️ Compromised Decision-Making

🛟 Missed Signals for Help

🧨 Poor Crisis Management

By doing that, I'll scare the managers among you enough to stop missing your 1:1s. If your manager has been skipping your 1:1s, send them this article.

⭐️ Reputational Damage

In the fast-paced industry that we work in, we want leaders to lead with a steady hand amid all the chaos. Engineers expect their managers to be a source of calm, stability, and consistency. This consistency in behavior and decision-making fosters a sense of trust and security in the team. It allows the team to focus and put the noise aside.

Missing one-on-ones has the opposite effect. It's erratic behavior. It does not send a message of consistency, stability, and trust. On the contrary, it paints the manager as disinterested, distracted, and disorganized.

Over time, missing 1:1s tarnishes the manager's reputation with their reports. The manager appears disengaged. He gets labeled as "MIA". The label propagates throughout the organization, and the reputation slowly evaporates.

🛡️ Hit on Trust and Credibility

Upstream of reputation are trust and credibility. Regular one-on-ones are fundamental to maintaining mutual trust. In 1:1s, managers get the opportunity to talk about what truly matters to their engineers and what is truly going on in their lives. It's about opening up and being vulnerable. Vulnerability builds trust. It sends the message that we all make mistakes, and it's important to learn from mistakes.

By skipping 1:1s, the manager signals that they do not value the report's time or concerns. They do not want to be frank with their reports and do not want to spend time debugging issues or insecurities. Over time, such behavior erodes the engineer's trust in their engineering manager. The engineer closes down and is not transparent with their manager, which eventually kills the relationship.

🤝 Weakened Team Morale and Engagement

As a manager, you are the face of the company to your team. In the capacity of an agent of the company, your reports interface with you, not your boss, HR, or anyone else. You. In their eyes, you are the company.

So, if you want them to feel appreciated by their employer, it's on you to make them. No one else can or will. The manager must explain the engineer's value to the organization.

Managers who miss their 1:1s don't take the time to show appreciation. As a result, their team starts to feel undervalued and disconnected. Disappointed reports will result in poor performance and the employees unwilling to go above and beyond.

⚖️ Compromised Decision Making

Managers rely on nuanced information to make decisions. A simple project staffing decision involves lots of steps and decisions. Here's a shallow demo of what usually goes in my head in terms of staffing projects:

Who is available to be the primary engineer on the project? Who else can help?

What is the rough complexity of the project? Is it difficult to implement?

Is there a good match between the available engineers and the project complexity?

What sort of work does the project entail? Does it require lots of stakeholder management?

Do the available engineers have the relevant skills?

Is the potential primary engineer a match from a career growth perspective? Would they like to work on this project?

If the first choice for a primary engineer does not take the project, are there alternatives on the team?

And so on. You get the point - there's so much nuance and context that each manager must consider when making any decision. Look at the list above: it requires off-the-cuff knowledge about the status of ongoing projects, the career goals of each engineer, available skills, project complexity, a rough feel for the work involved, etc.

Regarding knowledge of your team and their ambitions, you can only pick up these signals in open-ended conversations as a manager. Regular one-on-ones are perfect for exploring these topics. Managers who miss 1:1s end up making decisions based on incorrect, incomplete, or outdated data. In fast-paced environments, making decisions based on flawed data can harm the team's impact and the manager's career.

🛟 Missed Signals for Help

One-on-one meetings are the right environment to discuss personal challenges, such as health issues, family responsibilities, mental health struggles, burnout, big workload, etc. They often provide a private and safe space for individuals to share these concerns. In these nuanced situations, the manager must be present to pick up on the signals and act on them. At the very least, ask: How can I help?

By missing these regular check-ins, managers are unable to pick up the signals. They're unaware of their team members' struggles, which widens the drift between the situation on the ground and the manager's perception of it. This leads to compromised decision-making, unrealistic expectations from the team, and, eventually, attrition.

🧨 Poor Crisis Management

Conflicts are a byproduct of group work. They should be expected, especially with driven and passionate individuals. However, conflicts pose a risk for the team—they can quickly turn the environment sour. When they go unnoticed or unresolved for a longer time, they can easily escalate into larger issues.

Through regular check-ins, managers gauge the state of projects and team dynamics. Without talking to the team, the manager can't recognize the early signs of a crisis. Even worse, once the crisis unfolds, they cannot comprehend its full scope, which hinders their crisis management and remediation.

Crisis management requires quick action. However, a manager who doesn't communicate regularly with their team will not learn about a crisis until it has escalated. As a result, their response will be delayed, which will exacerbate the situation. On top of that, their communication will be off as they won't have the required information to de-escalate the situation.

That will further deepen the crisis and create confusion within the ranks.

🖖 That’s all folks

As always, I'm eager to hear from you, my readers! If you've read this far, you're awesome - drop me a message, I want to meet you!

Feel free to connect with me on LinkedIn or Twitter and send me a message. I respond to everyone, without exceptions.